Over the past eight months, Theatre Studies has been collaborating with the team at the University of Glasgow’s Archives and Special Collections to explore how performance methodologies might help tackle the problem of ‘archive anxiety’, the inherent barriers that can stand in the way of a deeper engagement with archives. As the work draws to a close, Research Assistant Sarah Gambell reflects on the project, its processes, and the value of imagination in bringing ‘hidden’ histories to life.

Archival Anxiety

Do you remember your first time in an archive? Your first time looking at a catalogue, or a finding aid? Was it simple, straightforward? Was it difficult to find what you were looking for? Did it keep you from coming back? What stands in the way of ease of navigation?

We call this ‘archival anxiety’; the inherent barriers that can stand in the way of a deeper engagement with archives.

The ‘Performing the Archive’ project set out to explore performance methodologies and special collections and how they can tackle this problem of archival anxiety. Funded by the University of Glasgow’s Learning and Teaching Development Fund, the project combines the skills of performers and archivists to create new pedagogical tools and models for object-based learning – or OBL – across the University.

As an experiential education approach, OBL directly benefits learners through its active approach; students do not simply learn from texts, but with and through texts and artefacts in modes of experiential, sensory and tactile engagement. However, there are inherent limits to such approaches both in terms of accessibility (archives and collections traditionally only foster to smaller groups; ‘archive anxiety’ may prevent students from engaging with collections; students may not be physically able to access archives) and perspective (institutionally, archives and collections have tended to claim neutrality, thus favouring one perspective and suppressing marginalised narratives such as BAME, LGBT, female and colonial experiences). ‘Performing the Archive’ deliberately drew on a pool of collaborators across subject areas – including History of Art, Theatre, Law, Medical Humanities, Social History and Slavery Studies – in order to provide interdisciplinary expertise for the thematic focus on ‘hidden’ histories and ‘minority’ narratives. As with many projects in this field, part of the aim is to develop a shared vocabulary and framework across disciplines.

The Workshops

We developed a series of workshops to gather a diverse group of participants to practically discuss how it involves acting methodologies to their courses. Working closely with the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities we recruited PhD students in relevant fields who wanted to share their insights about using archival materials in their own research.

There was a drastic rethinking of the scope of the project when it became obvious that the pandemic was going to seriously disrupt the facilitation of the workshops. The project shifted focus to explore how acting exercises and methodologies translate into online settings and actively enhance virtual learning environment approaches to OBL.

During the first practical session, participants investigated a variety of play texts, introducing several traditional acting exercises used to synthesise contextual information found within these texts. These were adapted to address and learn how to mitigate one of the overarching themes of ‘archival anxiety’, and engaged with the following guiding questions:

- How can performance based methodologies be applied to these issues in archives?

- How can educators use these strategies in our teaching?

- How can students use these strategies?

In this session, our acting consultants introduced the concept of ‘Imaginative Response’ which, in the context of this project, can be broadly defined as any creative response or output generated by integrating factual information, personal experience, reflection and imagination. First readings of play texts function like reconnaissance – gleaning things like atmosphere, tone and other superficial elements. The second reading allows the reader to delve in and get the undisputed factual elements – pulling out given circumstances, historical fact, information about characters, things that are unequivocally factual. Similar to archival texts, it can be challenging to read an extract of a play text as a singular scene. By not understanding the full text, the reader will be missing contexts that create a complete picture of the paradigm that the characters operate within. The reader then will need to use a certain level of imaginative response to unearth the hidden contexts.

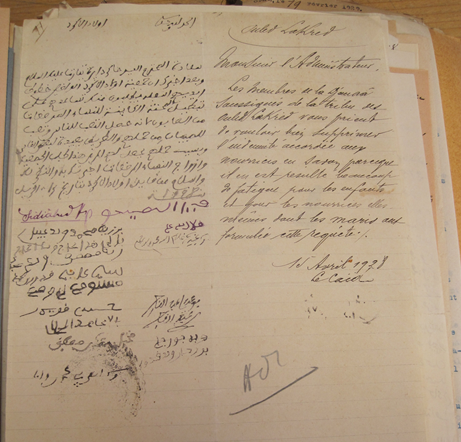

We also invited our participants to share with us examples of texts that they had previously used in teaching. One archival document we discussed was a petition document written in Arabic (with its French translation) that is used for a course on the history of medicine in the Middle East.

After discussing the context on the image, and situating it within the historical period, the image fueled a discussion about how archival materials represent the lives and ambitions of real people. Researchers who approach the information have to flesh out evidence which can be biased while still using imaginative response to filling the missing gaps in context.

The role of academic researchers can either take the form of passive reporters of the stories versus a role of active campaigners for the survival of endangered heritage. This depends on many factors and many layers of interpretation:

- Layers in the text shared

- Layers in the custodial history

- Layers in the interpretation

By combining performance methods and approaches to archives, we have started to see that play texts and primary source documents are not dissimilar – in the fact that the historian and the theatre maker is trying to create a world, context and bring to life voices hidden by many factors.

Final Playbook

As the project wraps up, we are bringing together all of the input that we have received from lectures, researchers, PhD students, and Masters’ students. The final output will be a framework developed with input from participants in the workshops that can be taken up in teaching to address archival anxiety, hidden histories and accessibility. This framework ‘playbook’ will be finalised in June 2021, and publically available to lecturers soon afterwards.

Three areas we continue to reflect on are:

- As educators, how can we demonstrate that an archive is made up of a lot of different layers? Like the scene-based approach, archival texts provide a snippet, and build up from that small part to understand the whole; there are layers of interpretation to every archival snippet.

- What is the makeup of students, and what kind of archives are they looking at? Based on the user background, there will be different interpretations of the text. How can the text reach a wider audience to influence them, and how exactly can this be undertaken?

- There is performativity of any written record. How can this best be understood using acting methodologies and exercises, such as Stanislavski’s Given Circumstances, or Hagen’s 6 Steps to Building a Character?

This project has provided an opportunity to further explore the nature of interdisciplinary learning, co-creation and the new zoom-based world we now navigate. The ideas that have started to blossom from our collaborative sessions already have a grounding in future projects and will continue to develop after this particular iteration ends in July. As we continue finalising our output, I will leave you with a reflection by our acting practitioner, Michael Howell:

Texts in an archive tend to be fragmented, incomplete and almost always written; constrained by language, grammar, era and influenced by opinion, gender and status. Seeking out new ways to give life to these texts for students in the here and now demands a creative approach. Unearthing hidden voices distorted by historical noise, the powerful and their subsequent interpreters is an important facet of engagement for those who are not represented by the records. ‘Performing the Archive’ has provided an opportunity to consider the relationship between fact, perspective and crucially the value of imagination as a critical third element when seeking to give life to a character or moment in history obscured by the available data. Exploring and subsequently evolving established performance techniques to develop a research approach that is rooted in creativity, imagination and collaborative practice has been a key element of the project. Guesswork based on an informed yet imaginative leap is often the final act and invaluable in breathing life into those obscured by our record of history.

Sarah Gambell is a PhD candidate in Information Studies and research assistant on the Performing the Archive project. Sarah has a background in archives and public history, and her doctoral research focuses on assessing digitisation methods used for preserving cultural heritage in conflict.

For further reading on related projects at the University of Glasgow see Rankin and Callaghan (2014/15) and Clark et al (2019). ‘Performing the Archive’ also draws heavily on the groundbreaking object-based multi-perspectivity model developed for ‘Call and Response: The University of Glasgow and Slavery’ (Rankin, Whyte et al 2019).