Dr Laura U. Marks, perhaps best known for her influential theory of haptic visuality, has built an impressive body of work focusing on embodiment in moving image culture. During her recent visit to the University of Glasgow she sat down with filmmaker and postgraduate student Max Breakenridge to discuss her work. Their talk touches on her thinking both past and present – from Islamic philosophy to the digital carbon footprint – and the field of moving image culture more generally.

When did you start making early connections of physicality in movies?

I got interested in experimental cinema early on: it might be because I studied art history as an undergraduate. I didn’t know anything about movies and found that experimental cinema does so much more with the form. Also, I studied dance, and when I started to take masters classes in film studies in the late 1980s (when the lacanian psychoanalytic paradigm was still in full swing) I wanted to talk about movies in terms of dance or bodies. When I discovered phenomenology through the work of Vivian Sobchack, that was just great: I’d never been able to believe in the theory of the subject in lacanian psychoanalysis: it was kind of aggressive against everyone. The theory of the subject in existential phenomenology just made so much more sense to me – I exist because you exist rather than I exist despite you. It makes it possible to think of kinaesthetic empathy, things like that. I must have been disposed to think in this embodied way and looking for a language for it: even before that I had started reading Deleuze’s cinematic books, which speak a lot to the body. I came up with this idea of haptic visuality, but that actually came from reading A Thousand Plateaus by Deleuze and Guattari. They talk about how in nomad art there is haptic space and abstract line, and the nature of haptic space which you explore up close rather than survey abstractly. That just made so much sense to me.

Dr Laura. U Marks is Grant Strate Professor at Simon Fraser University

Do you remember which experimental artists interested you?

A lot of the experimental work I saw was on analogue video, which has this beautiful soft liquidy colour to it, and which also loses quality when reproduced. Works by people like Bill Viola and Stan Brakhage. A new generation of American experimental filmmakers like Greta Snider and Jennifer Proctor also had a big effect on me – feminist experimental filmmakers who were using the material of film to speak to the materiality of the body, hand-processing it, scratching it, things like that.

How does that relate to digital? Do you think it has that same quality?

I think it can, and this is something that I’ve been insisting on since digital came around. There was this rhetoric when digital equipment became available in the mid-90s that digital media are immaterial, and I didn’t believe that for a second – it still surprises me that people buy into that idea. I wrote an essay about it in my second book, Video’s Body, Analogue and Digital. Digital video is a material medium: it has issues of storage, of resolution, it sees and hears in a certain way, and of course it breaks down in a very particular way. I’m actually fascinated by compression algorithms, because they try so hard to maintain what they think are the qualities of the image or sound that most people want – you see them struggling to approximate an idea of the general perception, such as edge recognition. Those artefacts that occur in a video that’s been compressed a couple of times, where there are extra edges – I think that’s hilarious.

Where do you see embodied moving images these days? You point to recent world cinema as using those techniques more.

When I started observing embodied techniques it was mostly in experimental works by diasporan filmmakers. You could see it in other places but that’s where I saw the innovation happening. But now there’s really nothing revolutionary in itself about a haptic image or haptic sound: they’re used in advertising all the time to make you feel close with the beer or the hamburger or whatever. But nevertheless, I do see a lot of works, both documentary and fiction, that use techniques that appeal to the embodied perception of the viewer, or that sometimes make a viewer feel like they’re going to merge with the scene. I saw a documentary last week by Leila Kilani, a Morroccan documentary and fiction filmmaker, about people who try to immigrate to Spain from Tangier. In it there are several shots at night that have a lot of reflections of the lights in the wet pavement, and it contributes to the feeling of disorientation that these refugees are experiencing, but also to the feeling of aspiration. I see it in a great many cinemas. And haptic visuality is not the only way.

Why do you find yourself more drawn to Islamic concepts rather than Western ones?

Initially I was attracted to Islamic theology and philosophy out of a feeling of resentment that these had been repressed from the western canon. That still defines much of my motivation, to show that there are concepts from Islamic or Arabic thought that were formative to European philosophy and that have been repressed. But there are some beautiful concepts that I think probably circulated in the early modern world – including Latin and Medieval philosophy – that were part of what we now call a philosophy of an enchanted world, the world before the great disenchantment of the enlightenment. Islamic philosophy of that period is really good at conceiving of the cosmos as a complex yet harmonious whole. We’re at a point now where people are tired of disenchantment, or starting to think, as Bruno Latour says, “we were never modern”, and that this repudiation of past world views is really overrated. In a time when people are perceiving that the world is interconnected, especially because of the environmental crisis, we understand that the world and the cosmos are an interrelated whole. It’s worth noting too that process philosophy is quite new to western philosophy, but that in the Muslim world it began much earlier, maybe in the 13th or 14th century. It’s really rich to immerse in a process philosophy that understands the things that are real are not objects but processes. It shifts your way of seeing the world.

You identify the material world being more aptly described as the physical world. Could you speak a bit on that?

I think it solves so many problems to speak of the physical world, which is composed of both matter and energy. It’s surprising to me that in the material turn in humanities studies, people didn’t think of matter as important dense historical stuff, but as inert as the stuff that we can grab. It suffers from the lack of process approach, as since energy is only visible in its effects and in time, it’s easy to forget that energy is the other side of matter. When you think about the physical world instead of the material world you realise, for example, the issue of the carbon footprint streaming media. To compare how much energy it takes to produce a DVD or a USB drive and the amount of energy it takes to stream a video you have to do a lot of complicated calculations – you have to know how much energy it takes to produce this object versus how much energy does it take to produce something seemingly immaterial. Once we include energy as part of the physical we get the complete picture.

I’m glad you brought up the idea of carbon footprints within our field as it isn’t something that is normally spoken about. Do you think it’s important for our field to address this?

I really do. I think it’s been the elephant in the room for us who work in moving image media. It really surprises me that no one has wanted to talk about it. But it’s right there, and at the same time streaming media makes it so much more accessible to us and there are all these new practices – from viral videos to live multiplayer gaming – which use huge amounts of energy. The cultural practices are fascinating and great, but we have to be aware of their carbon footprint and realise that it’s not only an aesthetic choice but a question of energy consumption. I’m hoping to make it fashionable and exciting to enjoy really small, low-resolution files. I want to start the small file media festival – doesn’t that sound great? There would be a limit to the size of your file, maybe there would be an award for the longest work with the smallest file size, and people could do super compressed works, animation, ASCII movies. That would be the fun side of a larger campaign to make people aware of how much energy we’re consuming when we stream media to our phones, and what is the source of that energy.

Do you think that responsibility lies within institutions or with the individual who either creates or views the work?

Both. Like the environmental movement in general, it has to be both: there is a mutual pressure. It’s important for individual activists and practitioners to raise each other’s awareness to start changing behaviour and putting pressure not only on our governments to switch to renewable energy but also on our streaming media service providers. According to Greenpeace those service providers actually want a reason to lobby governments to give them stricter criteria for how much energy they consume. On the one hand there’s a lot of activity on the part of individual makers and consumers but it has to be institutions, and some of the institutions are the companies themselves – Google and Apple and Huawei and Cisco – they’re working to innovate to save energy but they still want us to consume a lot, so we also need to have a movement to consume more carefully.

There’s an ideology that it’s immaterial, and corporations do everything to support that standpoint and not make us think about the materiality of our media.

Do you think that ties in with the perceived immateriality of digital?

Absolutely. People think “it floats from my phone onto the cloud!” That term “cloud” is brilliantly evil! People think “I have to plug my phone in” but rarely reflect that the cost of their plan partly reflects the cost of electricity at the server level. I think the cost of electricity should be much, much higher. There’s an ideology that it’s immaterial, and corporations do everything to support that standpoint and not make us think about the materiality of our media.

Where do you think we should be moving towards?

Late capitalist culture has been this gargantuan expansion of unnecessary products and ideas of wealth and vastness. But we have so much really dumb and useless stuff. I do think we need a contraction, an economic contraction, but mostly looking at contraction of consumption. I need to find a way to make this sound attractive and not like it’s an impoverishment. If you think of something like Netflix, there are thousands of shows available and a few of them might be really good, but you think there’s so much you can’t even stop to watch because you wonder if there’s something else that’s even better. We can say the same about any of our media built on this digital ideology of an endless archive, which actually isn’t endless, just large. I would like to have an economy of relative scarcity so that we really enjoy the preciousness of things.

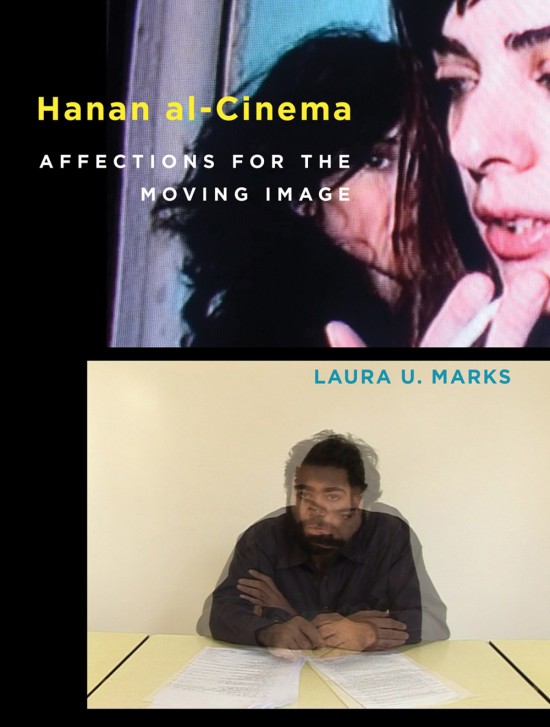

Dr Laura U. Marks works on media art and philosophy with an intercultural focus and programmes experimental media art for venues around the world. Her most recent books are Hanan al-Cinema: Affections for the Moving Image (MIT, 2015) and Enfoldment and Infinity: An Islamic Genealogy of New Media Art (MIT, 2010). With Dr. Azadeh Emadi of the University of Glasgow she is a founding member of the Substantial Motion Research Network. Dr. Marks is Grant Strate Professor in the School for the Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver.

Max Breakenridge is a Scottish filmmaker currently studying for an MSc in Filmmaking and Media Art at the University of Glasgow. His work is primarily concerned with nature, digital materiality and the body.

vimeo.com/maxbreakenridge

‘Luminous Images, Hidden in the Senses: Cultivating Cosmic Perception’ was a public lecture presented by Dr Laura U. Marks on Wednesday 6 November 2019 as part of the Material/Immaterial programme at the School of Culture and Creative Arts.